03-10-2021

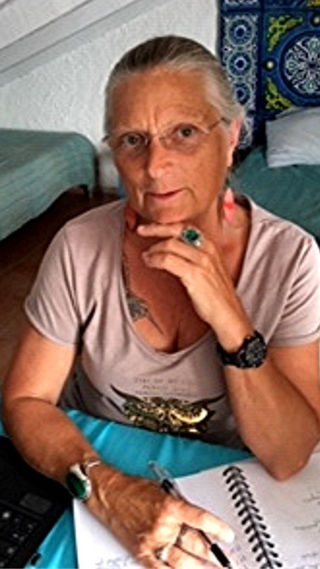

Suzanne Rancourt

When the Wind Stops

We were not allowed to stay with our family or community

where we fed our animals and grew our gardens, foraged

for wild food and medicines. Most of the harder changes

had come and gone. I only remember some of the old ways.

Papa doesn’t sing anymore.

He sleeps a lot - we don’t get to bathe like before

like when we would light candles around the tree --

stars of life – painted the ox horns red and black.

The desert sand could be molded to fit our bones for comfort.

The sidewalk tile is painted and unyielding. It doesn’t hurt me much

it hurts Papa. He sleeps a lot. We don’t eat much. Papa’s bones

have become angled with the new life of no life,

filthy feet, lice and soiled clothing. We have one cup, enamel,

it holds our sustenance - coins, grains of rice, sometimes tea.

Sometimes I pretend that I recognize people from our family,

our clan of wanderers, healers, singers – I run up to them

holding my cup, grabbing their hand as children do.

The men sometimes touch with the pads of their fingers around my lips

put gold in my cup and say they will buy me when I am older.

Papa cries to sleep. “We are hostages” he says, “to progress, engineers,

strangers with no color pressing black boxes to their faces paying gold

for our moments of no moments.” Papa sleeps on a pillow

stuffed with grime. The no-color-skin man touches my mouth and says

“You should never grow old” and presses the corner of my curved lip

with the same finger that presses the shiny button on the black box.

I am frightened and not frightened.

I remember sleeping in ox carts in cool desert nights with stars

our home was larger than all the palaces

we spun like turrets - arms up as pinnacles

in dresses and wraps of glitter and woven reds

brass and ivory arm bangles clacked and rung rhythmically

to the clay drums, click sticks, and gut–string.

I swirl loose tea in my chipped cup

like desert wind far away from sitting

in the sharp square of Papa’s sleeping hip, corner of

clay wall, painted tile floor - the backs of my legs are cool

getting longer. I am growing up

and the men will one day buy me because I could not stop

the progress of no life

living in the black box.

Summer Photos with the Boys at the Creek

I would not let go of defiance in my straight neck

squared-off look-you-in-the-eye stare unlike Emmett’s

knock-the-chip-off-my-shoulder cocked chin stare.

Mine was solid. The scar at the corner of my flat line lips

from the rim and tire iron incident made it so.

My chest is not out like Emmett’s hit-me-first chest

so I can hit-you-back

hit you back

hit you back

hit you back

My arms crossed, hands securely braced elbows into a square

the predictable square. Jack’s lips were softer than mine. He held his hand

like a beggar. My defiance carried me

through the “incident” at Sunday school

and the medical exam designed for defiant girls

with Sunday school incidents.

I had to learn about the half-body of the subtle

the non-committed-stance of the half-a-thought

and those who inferred arrogance

toward those who didn’t.

The Viewing

I want to write about you

because you are still here.

You were never a tall person. Your height

reflected the size of woodland People.

rounder now

but not in the photo as a young man pressing your back

into the Desoto’s closed trunk and the heel

of your boot hooked onto the curved, chrome bumper,

hands stuffed in slash pockets of your leather jacket -

Appalachian Jimmie Dean.

As a child I noticed your hands -

thick as Oak roots, wide as Bear paws -

were like your father’s. I noticed

when you handled a wrench, gripped the truck’s steering wheel,

or when you removed petrified baby rabbits

from the middle of the logging roads. Both of you

rounded, brown and small, crouched

before the rolling dust and grill of a chugging Detroit Diesel.

Hoisting with your Popeye arms

you swung yourself into the truck cab.

Your feet barely reached the clutch, brakes, and accelerator.

I asked, “Why did you do that?”

releasing emergency brakes with your 29” inseam leg

and slight grinding of gears, you said, “It ain’t easy bein’small.”

I didn’t think of you as being small.

Your gestures were always big

like the day you said, “C’mon, Suzy, Herbert’s killed the bears.”

You pulled your height upright,

charged across the lawn and headed next door.

You took the shortcut

through the spruce trees, down the banking to the road

that only us kids and dogs used.

I skip-trotted to keep up.

My calloused feet and stubbed toes kicked up patty-puffs of roadside sand.

Herbert lived next door. Already a crowd had congregated

to view bodies displayed side by side belly down

noses parallel. When Herbert talked

he sucked his teeth, the sound, almost

as sharp as snapping gum, he’d squint his eye opposite

the corner of the mouth that leered

when he sucked his teeth. As though

flesh was stuck between them.

“C’mon, Suzy, Herbert’s killed the bears”

and we went to see our relations

rendered waste by bad blood and heat. To see for ourselves

our family - a boar, a sow, and two cubs - the adults, largest in the state.

All lived behind our house on the mountain.

You showed me their tracks.

How they marked trees, rolled logs, where they fished.

When they mated in the hollow, they screamed like women.

You said they were harmless.

They had their space and we had ours.

Herbert killed the bears, sucked his teeth

and told how easy it was to kill babies,

how the male required more -

heavier trap, shorter chain, more bullets -

Herbert just killed.

You spit a puckering spit that shook the Earth

when it hit just inches from Herbert’s feet.

“C’mon, Suzy, we’ve seen enough.”

-from murmurs from the gate (Unsolicited Press 2019) selected by Spring 2022 Guest Editor, CMarie Fuhrman

Ms. Rancourt is Abenaki/Huron decent and is a multi-modal Expressive Arts Therapist with graduate degrees and certifications in psychology, creative writing, drug and alcohol recovery. Her first book of poetry, Billboard in the Clouds, Curbstone Press, received the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas First Book Award and is now in its 2nd printing, Northwestern University Press. Her second, murmurs at the gate, Unsolicited Press, released May 2019. Ms. Rancourt's 3rd book, Old Stones, New Roads, Main Street Rag Publishers, released 2021. Her 4th manuscript is scheduled for release from Unsolicited Press, Autumn 2023.