10-12-08

Brigit Pegeen Kelly

The Dragon

The bees came out of the junipers, two small swarms

The size of melons; and golden, too like melons,

They hung next to each other, at the height of a deer’s breast

Above the wet black compost. And because

The light was very bright it was hard to see them,

And harder still to see what hung between them.

A snake hung between them. The bees held up a snake,

Lifting each side of his narrow neck, just below

The pointed head, and in this way, very slowly

They carried the snake through the garden,

The snake’s long body hanging down, its tail dragging

The ground, as if the creature were a criminal

Being escorted to execution or a child king

To the throne. I kept thinking the snake

Might be a hose, held by two ghostly hands,

But the snake was a snake, his body green as the grass

His tail divided, his skin oiled, the way the male member

Is oiled by the female’s juices, the greenness overbright,

The bees gold, the winged serpent moving silently

Through the air. There was something deadly in it,

Or already dead. Something beyond the report

Of beauty. I laid my face against my arm, and there

It stayed for the length of time it takes two swarms

Of bees to carry a snake through a wide garden,

Past a sleeping swan, past the dead roses nailed

To the wall, past the small pond. And when

I looked up the bees and the snake were gone,

But the garden smelled of broken fruit, and across

the grass a shadow lay for which there was no source,

A narrow plinth dividing the garden, and the air

Was like the air after a fire, or before a storm,

Ungodly still, but full of shapes turning.

Windfall

There is a wretched pond in the woods. It lies on the north end of a

piece of land owned by a man who was taken to an institution years

ago. He was a strange man. I only spoke to him once. You can still

find statues of women and stone gods he set up in dark corners of the

woods, and sometimes you can find flowers that have survived the

collapse of the hidden gardens he planted. Once I found a flower

that looked like a human brain growing near a fence, and it took my

breath away. And once I found, among some weeds, a lily white as

snow....No one tends the land now. The fences have fallen and the

deer grown thick, and the pond lies black, the water slowly

thickening, the banks tangled with weeds and grasses. But the pond

was very old even when I first came upon it. Through the trees I

saw the dark water steaming, and smelled something sweet rotting,

and then as I got closer, I saw in the dark water shapes, and the

shapes were golden, and I thought, without really thinking, that I

was looking at the reflections of leaves or of fallen fruit, though

there were no fruit trees near the pond and it was not the season for

fruit. And then I saw that the shapes were moving, and I thought

they moved because I was moving, but when I stood still, still they

moved. And still I had trouble seeing. Though the shapes took on

weight and muscle and definite form, it took my mind a long time

to accept what I saw. The pond was full of ornamental carp, and they

were large, larger than the carp I have seen in museum pools, large

as trumpets, and so gold they were almost yellow. In circles, wide

and small, the plated fish moved, and there were so many of them

they could not be counted, though for a long time I tried to count

them. And I thought of the man who owned the land standing where

I stood. I thought of how years ago in a fit of madness or high faith

he must have planted the fish in the pond, and then forgotten them,

or been taken from them, but still the fish had grown and still they

thrived, until they were many, and their bodies were fast and bright

as brass knuckles or cockscombs. I tore pieces of my bread and

threw them at the carp, and the carp leaped, as I have not seen carp

do before, and they fought each other for the bread, and they were

not like fish but like gulls or wolves, biting and leaping. Again and

again, I threw the bread. Again and again, the fish leaped and

wrestled. And below them, below the leaping fish, near the bottom

of the pond, something slowly circled, a giant form that never rose

to the bait and never came fully into view, but moved patiently in

and out of the murky shadows, out and in. I watched that form, and

after the bread was gone and after the golden fish had again grown

quiet, my mind at last constructed a shape for it, and I saw for the

space of one moment or two with perfect clarity, as if I held the

heavy creature in my hands, the tarnished body of an ancient carp.

A thing both fragrant and foul. A lily and a man’s brain bound

together in one body. And then the fish was gone. He turned and

the shadows closed around him. The water grew blacker, and the

steam rose from it, and the golden carp held still, still uncountable.

And softly they burned, themselves like flowers, or like fruit blown

down in an abandoned garden.

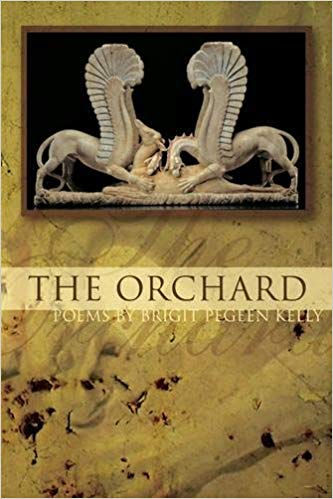

-from The Orchard

BIO: Brigit Pegeen Kelly was one of America’s most strikingly original contemporary poets. Born in Palo Alto, California, Kelly received some of American poetry’s most prestigious honors, including a Discovery/the Nation Award, the Yale Younger Poets Prize, a Whiting Writers Award, and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Academy of American Poets.

Kelly was the author of To the Place of Trumpets (1987), selected by James Merrill for the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize; Song (1995), winner of the Lamont Poetry Prize of the Academy of American Poets; and The Orchard (2004), a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Award in Poetry, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Pulitzer Prize. In poems that frequently turn nature into a kind of myth, Kelly exposes both the glory and menace of animal and human life, birth and death, stasis and change. Over three books, she has created a style at once richly imagined and emotionally complex. Praising Kelly’s work, poet Carl Phillips noted that “her poems are like no one else’s—hard and luminous, weird in the sense of making a thing strange, that we at last might see it, poems that from book to book show a strength that flexes itself both formally and in terms of content, in ways that continue to, at equal turns, teach and surprise.”

“The religious imagination is part and parcel of Kelly’s work,” commented Stephen Yenser in the Yale Review. “Always in touch with the so-called natural world, her poems nonetheless present it ineluctably in Christian terms, whose implicit verities she invariably calls into question.” Kelly’s earliest book, To the Place of Trumpets, includes several poems that reflect her Catholic upbringing, including stained-glass angels coming to life. At times adopting a child’s point of view, the book is a detailed vision of a world beginning to take shape unto itself; it points towards the larger themes and bigger, stranger landscapes that characterize her second and third books. While continuing to explore ritual, belief, and doubt, Kelly’s later work has won praise for its stark, even shocking, portrayals of evil and transcendence. Using a menagerie of animals both real and invented, Kelly’s later work explores the slippage between fact and fantasy. According to Carl Phillips, Kelly’s self-imposed task has been to “investigate why the world is so protean, pitching our human desire to empirically know a thing against a very real—and in the world of Kelly’s poems—an otherworldly resistance to so-called rational thinking. The title poem in Song associates a haunting tune with the brutal killing of a girl’s pet goat by a group of boys. The poem “appropriately introduces the reader to some of the unexpected and compelling ways the poet achieves meaning and effect through the agency of music,” wrote Robert Buttel in American Book Review.

Comparing Song and The Orchard in the Guardian, Fiona Sampson noted that while they share similar themes and structures, The Orchard’s “diction is thicker, less elegant. The poems are more clearly narrative and populated: the figure of a boy, in particular, recurs. By now it is clear that goat, doe, and all the rest are not merely statuary but animated myths. Kelly’s Orchard is the dangerous grove where transformations happen.”

Kelly taught at various colleges and universities, including the University of California-Irvine, Purdue University, Warren Wilson College, and the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. She died in 2016.

The Orchard, a review by Tony Leuzzi

Brigit Pegeen Kelly's poems are like rare birds: strange and wonderful. More closely aligned with the offbeat brilliance of Dylan Thomas than, say, the confessional voice of Anne Sexton, Kelly's intricately-patterned poems inhabit the fertile field of elegy––a subject that, through its obsessive reiteration, suggests that each new poem is a dazzling revision of the ones that came before it. If I'm saying that Kelly tends to write the same poem over and over again, this tendency enables her to achieve the sort of depth and vision most poets only dream of. As a book, then, The Orchard is a coherent statement on the experience of loss, or––more precisely––how one attempts to understand this experience through the powerful yet unstable realities of the physical world. Whether the voice in her poems is pondering the "heavy" absence of a statue's arms ("The Sparrow's Gate") or discovering the problematic relationship between likenesses (such as "mute the birds. Not like birds at all" in "Two Boys"), or ruminating on the mind's tendency to sculpt its own approximate reality (as the artist does, using a "poor dog" to carve "Out of the blackest of black stones a female wolf" in "The Wolf"), it is always aware that, in its fumbling toward articulation, it is attempting to fill space, to create matter where there is only emptiness.

Perhaps it is this very anxiousness that accounts for the conspicuous fullness of Kelly's poems. Her long, loose hexameter lines aurally and visually distinguish her from the shorter, more concise expressions of her contemporaries. Moreover, within these lines, there is a tendency to bead together disparate images, suggesting that everything is connected: in "The Satyr's Heart," for example, the voice notes "…There is the smell of fruit/And the smell of wet coins..." Like Whitman's "inclusive" verse, her cadenced lines are patterned on parallel structure and figures of repetition because these devices allow her to be expansive. Unlike Whitman, however, Kelly's expansiveness is filled with doubt, with dis-ease. In "Brightness from the North," one of The Orchard's most moving poems, a seven-line enumeration about the vegetation in a garden is immediately followed by the admission that "…the day will be empty/Because you are no longer in it…"

Most people reading this volume will attempt to compare it to Kelly's previous book, 1994's Song––a tour de force that established Kelly as a sui generis voice in contemporary poetry. While there is no question that both books are compatible in theme, tone, and diction, The Orchard finds Kelly moving further away from stanzaic forms. The notable exceptions here are "Sheet Music" (quatrains) and "Midwinter" (tercets), both of which are as powerful as some of Song's best poems. Nonetheless, the prevailing structure throughout is on the aforementioned loose hexameter that accumulates beyond twenty-five lines. An untrained eye might mistake some of these poems (like "The Dance" or "The Sparrow's Gate") for prose, since their lines are so deliciously long. To make this mistake, however would be to disregard Kelly's consistent integrity to line endings and her impeccable ear for rhythms made possible through line breaking. One need only consider the four actual prose poems in The Orchard to understand the difference.

Scattered evenly throughout the book, these poems share with the verse a preoccupation with the internal struggle between presence and absence, and they boast much of the same rhetorical brilliance of the lined poems. However, the prose poems are, perhaps, an uninitiated reader's best way into the book, since their structure seems to have allowed Kelly to relax and write more directly. In "The Foreskin," for example, she states her theme more plainly than she does in any other section of the book: the word did not seem to resemble the thing I held in hand, as words so often do not resemble the things they represent, or what we imagine them to represent; words can even destroy in their saying the very thing for which they stand.

While the act of planting her newborn child's foreskin in the garden is made clear, the poem, unlike so many contemporary prose poems, is not driven by action or event. Very much like the verse, an understated act precipitates observation, rumination and ultimately revelation.

In the context of The Orchard, the prose pieces usually function as interludes for the more complexly-designed lined poems. However, one of these prose poems should be regarded among the book's best poems. Consider the gorgeous, natural music of "Windfall," which moves organically from the voice's perception of a "wretched pond in the woods" to her shock and delight in finding the pond is filled with "ornamental carp...large as trumpets." The prose here moves seamlessly from observation to observation, braiding compound figures and seemingly incompatible imagery into a coherent microcosm of the entire collection itself.