04-10-2024

Ellen McGrath Smith

THE ANNUNCIATION

after the painting by Henry Ossawa Tanner

There was so much Robe, and all of it weighed,

melted-candlewax drippings of dun-colored

Robe: How on earth could she ever say “no”?

In the crack in the wall, she had seen her own maidenhood,

bloodied yet somehow intact, and the fact that the rug

at her feet buckled there, in the middle, was only more proof

that this life was a series of doings, undoings.

What flag can a teenage girl fly that isn’t already translucent,

x-rayed by the sun, its diurnal laws, golden gavels, ramrod

pillars of heat and becoming? She isn’t quite sure,

you can see that. And so men adore her and force

all their women to look up like that and accept

that a “yes” is pro forma, and only a “no” carries

weight even greater than all those tan robes. Piled

black crepe in one corner, glowing urns in the other.

Crow’s feathers, crone’s ash in the shadowy arches

where her mind's gone to live.

MINOR CASUALTY, 2003

Just as she began to walk boldly in daylight,

as she began to hear what, before,

there were laws against hearing

and, listening, walked boldly

past figures in black

who were biting their tongues—

as the swollen hips of buses turned corners,

she dangled her arms like she actually had power

and jangled her keys—metal army—

remembering milk-carton armadas

she'd floated in gutters, a child too devoted

to the mission, too painted in mud

to hike up her jeans by the beltloop.

The father-mechanics amazed her, the way

in the middle of making machinery work,

in the middle of wrenches and drills

and cement—they would hike up their jeans

by the beltloop, remembering their bodies

but never so long that the work went undone.

(Pirates once hid in her pockets, prepared

to invade at her cough, her command,

while nightsticks and whiteness

kept her borders safe from the riots of '68,

and in that safety, she rehearsed a courage

no one wanted or needed —)

Garbage trucks thudding like tanks

through the alley and weeping

their maggoty juice through the canvas,

competing, competing with lilac.

As she marched boldly against the war

wearing postures from imagined wars,

passing cars shot out obscenities, blood

vessels throbbed in unsheathed bayonets,

jonquils bobbed in windowboxes,

bunting—red, white, blue—kept up its blithe

though frightened laughter,

old women dropped their satin scarves

of prayer from robberbaron balconies.

The way satin sipped the light of Easter's death

and resurrection made her stop and stare—

neat green awnings, gentle screen doors, malt-scent

of pushmowers hissing and snapping the small stalks

of lawn; ice cubes and mint in a neighbor's glass tumbler;

an atomizer doubled in a mirror, candies wrapped

in pastel netting, hair ribbons, crisp white-picket

settings; lavender—her mother—the lotion

her mother had very soft skin—

And her swagger slipped off, though she kept on

walking. It pooled on the ground near a curb.

MEN ARE BACK—the headlines claimed;

she hadn't known they'd gone away.

Mechanics fathers firemen soldiers

—a clatter that grew louder: choppers?

tomahawks? syncopated with loud sun

beyond the sight and strength of anyone.

They do, they fix, they move the earth

around. Bunker busters, shock and awe,

ads celebrating their re-won erections.

They wanted her courage but not her conviction.

The satin scarves twisted, mid-air, into hawks.

FEBRUARY WAS ONLY HALF OVER

February was only half over, and so I decided to roll all the change.

I emptied all the tin cans and jars; the bedspread was covered in coins.

I decided to pawn the wedding ring. On the bus after,

I cried, thinking how the jeweler shaped the love-knot out of wax,

then poured the gold over. I paid the light bill with that.

Those rolling tubes ran out, and so I decided to count out the coins,

then stack and wrap units in foil:

50 pennies=one half-dollar

40 nickels=$2

50 dimes=$5

40 quarters=$10

Soon after, I would sell the antique dental cabinet.

On the Internet, I pretended I knew what I had.

That took care of half my June expenses.

This was the year the cost of cigarettes spiked.

I bought a rolling machine and spent 2004

rolling pennies, nickels, quarters, dimes, tobacco.

I realized, after rolling coins, that my hands had touched everyone

somehow. Some people soak coins in alcohol first—germs—

but getting sick was the last thing on my mind.

Filling every sleeve with my upright middle finger,

I was getting through the month and touching everyone.

-from Nobody's Jackknife selected by Sheila Fiona Black, Spring 2024 PoemoftheWeek.com Guest Editor

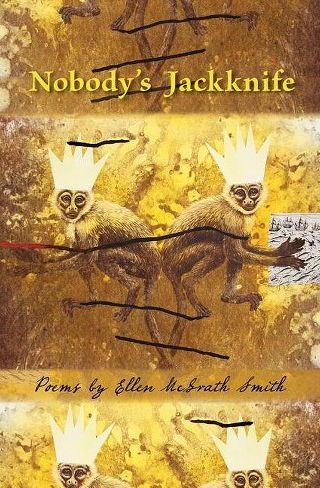

Ellen McGrath Smith teaches at the University of Pittsburgh and in the Carlow University Madwomen in the Attic program. She holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Pittsburgh and a PhD in Literature from Duquesne University. Her poetry has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Los Angeles Review, Quiddity, Cimarron, and other journals, and in several anthologies, including Beauty Is a Verb: The New Poetry of Disability and the Rabbit Ears: TV Poems. Smith has been the recipient of an Orlando Prize from A Room of Her Own Foundation, an Academy of American Poets award, a Rainmaker Award from Zone 3 magazine, and a 2007 Individual Artist grant from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts. Her work has been recognized with two Pushcart nominations, two Best New Poets nominations, and a Best of the Net nomination. Her second chapbook, Scatter, Feed, was published by Seven Kitchens Press in the fall of 2014, and her full-length collection, Nobody's Jackknife, was in fall 2015 by the West End Press.

Visit Ellen's blog, Purposeful Groping, here.